The Great Fire of 1871

When people think back to historical fires of great proportions in the late 19th century, the Chicago fire of 1871 normally pops to the top of the list. While that blaze certainly should rank near the top of the list, northeastern Wisconsin suffered an even larger conflagration at exactly that same time in October. Chicago claimed the newspaper headlines due to its massive property loss, but the Wisconsin fire claimed a greater number of lives and burned over a far greater area.

"At the time of the Wisconsin incident, the popular theory was that the fire started on the west side of the Bay of Green Bay then embers were windborne all the way across the bay to ignite further burning on the east side of the bay," said New Holstein Historical Society's annual meeting guest speaker David Siegel of the Green Bay Metropolitian Fire Department. "We know now, from historical investigation, that the Wisconsin fire was actually three fires which started seperately in the same general area."

Siegel said that conditions in 1871 were almost ideal for a large surface fire. A prolonged dry period had rendered grasslands, some swampy areas, and forest area floors dry and susceptible to burning. The forested areas were also filled with "slash", the remnants of timber harvesting. Limbs, branches, sawdust, anything that was not usable as a building material and was thus left behind when a tree was taken down, to be used for lumber, comprised the on-ground waste called slash.

The western lobe of the Wisconsin fire area is probably best known as the Peshtigo Fire. It burned northward on the west side of the bay. Two other, smaller, lobes burned on the east side of the bay starting north of the community of Green Bay and heading as far north as the Door County/Kewaunee County line, then east toward Lake Michigan. "Flames did not jump the bay," stated Siegel, "these fires all started on their own at seperate points then were wind driven on their paths of destruction."

The winds were actually the most crutial factor in the advancement of the fires. Describing the winds on those October days as being much like the straightline winds we experience today, Siegel said that with fierce winds pushing the fires foward in combination with the abundance of dry combustible materials, including structures such as houses and places of business made of timber, in the fire path, the blazes quickly became "fire storms". On the west side of the bay Peshtigo suffered great property loss as well as loss of lives. On the east side, communities like New Franken and Williamsonville were obliterated by the sweeping inferno.

Siegel stated that loss of life was great in the Wisconsisn fire area because there was no place for people to go to get away from the fire. Everything in the fire's path was combustible. There were few places to hide. Some folks sought refuge in a river and inside well sites, but many of those people also succumbed due to the massive heat that accompanied the fires. Superheated air was pulled into people's lungs destroying soft internal tissue and causing death. Some residents made their way to a river and found refuge from the flames, but after emerging from the water when the fire had passed, had no way of drying out or warming up. Many contracted various maladies associated from the "chill" they sustained on what became a cold October day in the fire's aftermath. Some of those maladies, like pneumonia, led to further deaths.

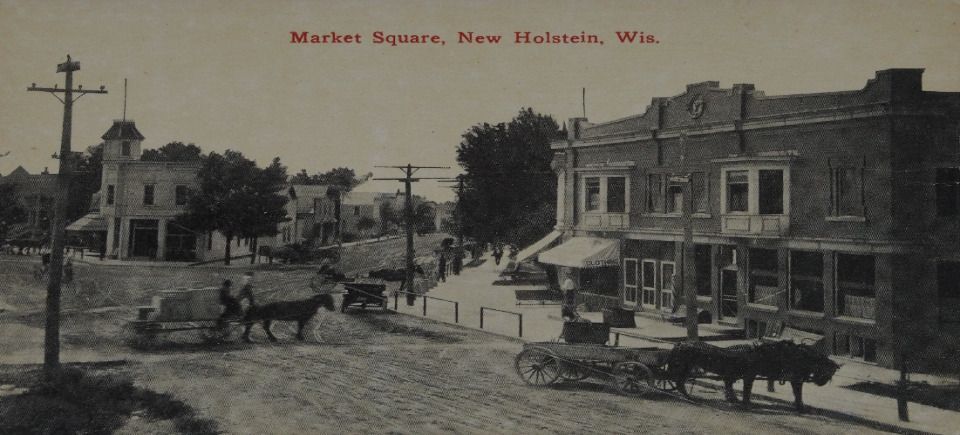

While the tale of the "Great Fire of 1871" is a somewhat grim one, Siegel stated that some good did come from it. Survivors stayed in the area and rebuilt. Non flammable components like rock and brick became preferred building materials, better clean up and disposal practices were incorporated into forestry management, and communities began to think about methods of fire supression should situations necessitate it.

And a hundred miles, or so, to the south, Chicago managed to pull itself together and survive also.

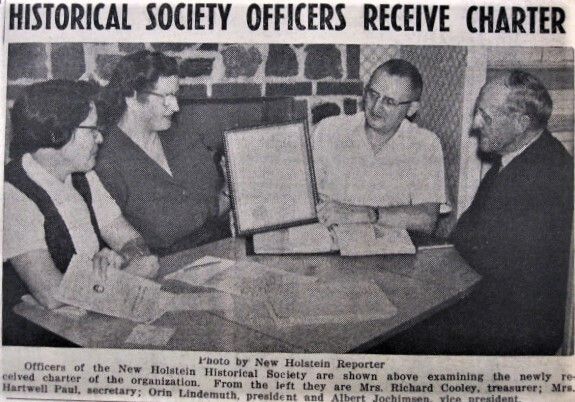

Following Siegel's address, a short NHHS annual meeting was held with the main point of business being the election of three members to the NHHS Board of Directors. Incumbents Donna Schneider, Linda Schneidewind, and Grace Flora were all re-elected to three year terms.